Lecture 13 - Pulling Back Partitions

Last time we studied meets and joins of partitions. We observed an interesting difference between the two.

Suppose we have partitions \(P\) and \(Q\) of a set \(X\). To figure out if two elements \(x , x' \in X\) are in the same part of the meet \(P \wedge Q\), it's enough to know if they're the same part of \(P\) and the same part of \(Q\), since

\[ x \sim_{P \wedge Q} x' \textrm{ if and only if } x \sim_P x' \textrm{ and } x \sim_Q x'. \]

Here \(x \sim_P x'\) means that \(x\) and \(x'\) are in the same part of \(P\), and so on.

However, this does not work for the join!

\[ \textbf{THIS IS FALSE: } \; x \sim_{P \vee Q} x' \textrm{ if and only if } x \sim_P x' \textrm{ or } x \sim_Q x' . \]

To understand this better, the key is to think about the "inclusion"

\[ i : \{x,x'\} \to X , \]

that is, the function sending \(x\) and \(x'\) to themselves thought of as elements of \(X\). We'll soon see that any partition \(P\) of \(X\) can be "pulled back" to a partition \(i^{\ast}(P)\) on the little set \( \{x,x'\} \). And we'll see that our observation can be restated as follows:

\[ i^{\ast}(P \wedge Q) = i^{\ast}(P) \wedge i^{\ast}(Q) \]

but

\[ \textbf{THIS IS FALSE: } \; i^{\ast}(P \vee Q) = i^{\ast}(P) \vee i^{\ast}(Q) . \]

This is just a slicker way of saying the exact same thing. But it will turn out to be more illuminating!

So how do we "pull back" a partition?

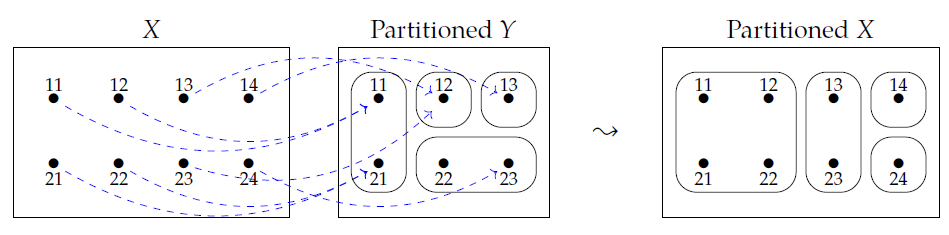

Suppose we have any function \(f : X \to Y\). Given any partition \(P\) of \(Y\), we can "pull it back" along \(f\) and get a partition of \(X\) which we call \(f^{\ast}(P)\). Here's an example from the book:

For any part \(S\) of \(P\) we can form the set of all elements of \(X\) that map to \(S\). This set is just the preimage of \(S\) under \(f\), which we met in Lecture 9. We called it

\[ f^{\ast}(S) = \{x \in X: \; f(x) \in S \}. \]

As long as this set is nonempty, we include it our partition \(f^{\ast}(P)\).

So beware: we are now using the symbol \(f^{\ast}\) in two ways: for the preimage of a subset and for the pullback of a partition. But these two ways fit together quite nicely, so it'll be okay.

Summarizing:

Definition. Given a function \(f : X \to Y\) and a partition \(P\) of \(Y\), define the pullback of \(P\) along \(f\) to be this partition of \(X\):

\[ f^{\ast}(P) = \{ f^{\ast}(S) : \; S \in P \text{ and } f^{\ast}(S) \ne \emptyset \} . \]

Puzzle 40. Show that \( f^{\ast}(P) \) really is a partition using the fact that \(P\) is. It's fun to prove this using properties of the preimage map \( f^{\ast} : P(Y) \to P(X) \).

It's easy to tell if two elements of \(X\) are in the same part of \(f^{\ast}(P)\): just map them to \(Y\) and see if they land in the same part of \(P\). In other words,

\[ x\sim_{f^{\ast}(P)} x' \textrm{ if and only if } f(x) \sim_P f(x') \]

Now for the main point:

Proposition. Given a function \(f : X \to Y\) and partitions \(P\) and \(Q\) of \(Y\), we always have

\[ f^{\ast}(P \wedge Q) = f^{\ast}(P) \wedge f^{\ast}(Q) \]

but sometimes we have

\[ f^{\ast}(P \vee Q) \ne f^{\ast}(P) \vee f^{\ast}(Q) . \]

Proof. To prove that

\[ f^{\ast}(P \wedge Q) = f^{\ast}(P) \wedge f^{\ast}(Q) \]

it's enough to prove that they give the same equivalence relation on \(X\). That is, it's enough to show

This looks scary but we just follow our nose. First we rewrite the right-hand side using our observation about the meet of partitions:

Then we rewrite everything using what we just saw about the pullback:

\[ f(x) \sim_{P \wedge Q} f(x') \textrm{ if and only if } f(x) \sim_P f(x') \textrm{ and } f(x) \sim_Q f(x'). \]

And this is true, by our observation about the meet of partitions! So, we're really just stating that observation in a new language.

To prove that sometimes

\[ f^{\ast}(P \vee Q) \ne f^{\ast}(P) \vee f^{\ast}(Q) , \]

we just need one example. So, take \(P\) and \(Q\) to be these two partitions:

They are partitions of the set

\[ Y = \{11, 12, 13, 21, 22, 23 \}. \]

Take \(X = \{11,22\} \) and let \(i : X \to Y \) be the inclusion of \(X\) into \(Y\), meaning that

\[ i(11) = 11, \quad i(22) = 22 . \]

Then compute everything! \(11\) and \(22\) are in different parts of \(i^{\ast}(P)\):

\[ i^{\ast}(P) = \{ \{11\}, \{22\} \} . \]

They're also in different parts of \(i^{\ast}(Q)\):

\[ i^{\ast}(Q) = \{ \{11\}, \{22\} \} .\]

Thus, we have

\[ i^{\ast}(P) \vee i^{\ast}(Q) = \{ \{11\}, \{22\} \} . \]

On the other hand, the join \(P \vee Q \) has just two parts:

\[ P \vee Q = \{\{11,12,13,22,23\},\{21\}\} . \]

If you don't see why, figure out the finest partition that's coarser than \(P\) and \(Q\) - that's \(P \vee Q \). Since \(11\) and \(22\) are in the same parts here, the pullback \(f^{\ast}(P) \vee f^{\ast}(Q) \) has just one part:

\[ f^{\ast}(P \vee Q) = \{ \{11, 22 \} \} . \]

So, we have

\[ f^{\ast}(P \vee Q) \ne f^{\ast}(P) \vee f^{\ast}(Q) \]

as desired. \( \quad \blacksquare \)

Now for the real punchline. The example we just saw was the same as our example of a "generative effect" in Lecture 12. So, we have a new way of thinking about generative effects: the pullback of partitions preserves meets, but it may not preserve joins!

This is an interesting feature of the logic of partitions. Next time we'll understand it more deeply by pondering left and right adjoints. But to warm up, you should compare how meets and joins work in the logic of subsets:

Puzzle 41. Let \(f : X \to Y \) and let \(f^{\ast} : PY \to PX \) be the function sending any subset of \(Y\) to its preimage in \(X\). Given \(S,T \in P(Y) \), is it always true that

\[ f^{\ast}(S \wedge T) = f^{\ast}(S) \wedge f^{\ast}(T)? \]

Is it always true that

\[ f^{\ast}(S \vee T) = f^{\ast}(S) \vee f^{\ast}(T)? \]

To read other lectures go here.

Click here to read the original discussion.

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.